Review of Limtis Solve Each of the 17 Problems on Limits

Calculus, originally called minute calculus or "the calculus of infinitesimals", is the mathematical written report of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the report of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithmetic operations.

It has ii major branches, differential calculus and integral calculus; differential calculus concerns instantaneous rates of change, and the slopes of curves, while integral calculus concerns accumulation of quantities, and areas under or between curves. These two branches are related to each other by the fundamental theorem of calculus, and they make employ of the fundamental notions of convergence of infinite sequences and infinite series to a well-defined limit.[1]

Infinitesimal calculus was developed independently in the tardily 17th century by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.[2] [3] Later work, including codifying the idea of limits, put these developments on a more solid conceptual footing. Today, calculus has widespread uses in science, engineering, and economics.[four]

In mathematics education, calculus denotes courses of elementary mathematical assay, which are mainly devoted to the written report of functions and limits. The word calculus is Latin for "small pebble" (the atomic of calx, significant "stone"). Considering such pebbles were used for counting out distances,[five] tallying votes, and doing abacus arithmetic, the word came to mean a method of ciphering. In this sense, it was used in English at least as early equally 1672, several years prior to the publications of Leibniz and Newton.[6] (The older meaning nonetheless persists in medicine.) In improver to the differential calculus and integral calculus, the term is besides used for naming specific methods of calculation and related theories, such as propositional calculus, Ricci calculus, calculus of variations, lambda calculus, and process calculus.

History

Modern calculus was adult in 17th-century Europe by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (independently of each other, kickoff publishing effectually the same time) but elements of it appeared in ancient Greece, and then in Communist china and the Center East, and still later again in medieval Europe and in Bharat.

Ancient precursors

Arab republic of egypt

Calculations of volume and surface area, one goal of integral calculus, can be plant in the Egyptian Moscow papyrus (c. 1820 BC), just the formulae are uncomplicated instructions, with no indication as to how they were obtained.[vii] [8]

Hellenic republic

Laying the foundations for integral calculus and foreshadowing the concept of the limit, aboriginal Greek mathematician Eudoxus of Cnidus (c. 390 – 337 BCE) developed the method of exhaustion to prove the formulas for cone and pyramid volumes.

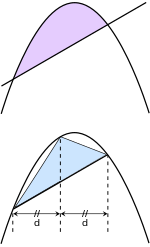

During the Hellenistic period, this method was further developed by Archimedes, who combined it with a concept of the indivisibles—a precursor to infinitesimals—allowing him to solve several bug at present treated by integral calculus. These problems include, for example, calculating the center of gravity of a solid hemisphere, the middle of gravity of a frustum of a circular paraboloid, and the surface area of a region divisional by a parabola and one of its secant lines.[ix]

China

The method of exhaustion was later discovered independently in China by Liu Hui in the 3rd century AD in order to find the area of a circle.[10] [11] In the 5th century AD, Zu Gengzhi, son of Zu Chongzhi, established a method[12] [13] that would later exist called Cavalieri'due south principle to observe the volume of a sphere.

Medieval

Middle Due east

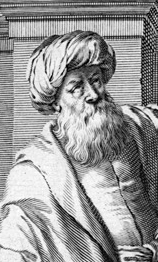

Alhazen, 11th-century Arab mathematician and physicist

In the Middle East, Hasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (c. 965 – c. 1040 CE) derived a formula for the sum of fourth powers. He used the results to bear out what would now be called an integration of this office, where the formulae for the sums of integral squares and fourth powers allowed him to calculate the volume of a paraboloid.[xiv]

India

In the 14th century, Indian mathematicians gave a non-rigorous method, resembling differentiation, applicable to some trigonometric functions. Madhava of Sangamagrama and the Kerala School of Astronomy and Mathematics thereby stated components of calculus. A complete theory encompassing these components is at present well known in the Western world as the Taylor series or infinite series approximations.[15] [16] All the same, they were not able to "combine many differing ideas nether the 2 unifying themes of the derivative and the integral, show the connection between the 2, and turn calculus into the nifty problem-solving tool nosotros take today".[14]

Modern

The calculus was the first achievement of modern mathematics and it is difficult to overestimate its importance. I think it defines more unequivocally than annihilation else the inception of modern mathematics, and the system of mathematical assay, which is its logical development, yet constitutes the greatest technical advance in verbal thinking.

—John von Neumann[17]

Johannes Kepler's work Stereometrica Doliorum formed the basis of integral calculus.[18] Kepler developed a method to calculate the area of an ellipse by calculation upward the lengths of many radii fatigued from a focus of the ellipse.[19]

A pregnant piece of work was a treatise, the origin being Kepler'south methods,[nineteen] written by Bonaventura Cavalieri, who argued that volumes and areas should exist computed as the sums of the volumes and areas of infinitesimally thin cross-sections. The ideas were like to Archimedes' in The Method, just this treatise is believed to have been lost in the 13th century, and was only rediscovered in the early 20th century, and so would take been unknown to Cavalieri. Cavalieri's piece of work was not well respected since his methods could lead to erroneous results, and the minute quantities he introduced were disreputable at first.

The formal study of calculus brought together Cavalieri's infinitesimals with the calculus of finite differences developed in Europe at around the aforementioned fourth dimension. Pierre de Fermat, challenge that he borrowed from Diophantus, introduced the concept of adequality, which represented equality upwards to an infinitesimal fault term.[20] The combination was achieved by John Wallis, Isaac Barrow, and James Gregory, the latter two proving predecessors to the second fundamental theorem of calculus around 1670.[21] [22]

The product rule and chain rule,[23] the notions of higher derivatives and Taylor series,[24] and of analytic functions[25] were used past Isaac Newton in an idiosyncratic notation which he applied to solve problems of mathematical physics. In his works, Newton rephrased his ideas to suit the mathematical idiom of the fourth dimension, replacing calculations with infinitesimals by equivalent geometrical arguments which were considered beyond reproach. He used the methods of calculus to solve the problem of planetary motion, the shape of the surface of a rotating fluid, the oblateness of the globe, the move of a weight sliding on a cycloid, and many other bug discussed in his Principia Mathematica (1687). In other work, he adult series expansions for functions, including partial and irrational powers, and information technology was articulate that he understood the principles of the Taylor series. He did not publish all these discoveries, and at this time infinitesimal methods were however considered disreputable.[26]

These ideas were arranged into a true calculus of infinitesimals past Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who was originally accused of plagiarism past Newton.[27] He is now regarded as an contained inventor of and contributor to calculus. His contribution was to provide a clear set up of rules for working with infinitesimal quantities, assuasive the computation of second and higher derivatives, and providing the product rule and chain rule, in their differential and integral forms. Unlike Newton, Leibniz put painstaking effort into his choices of annotation.[28]

Today, Leibniz and Newton are usually both given credit for independently inventing and developing calculus. Newton was the get-go to apply calculus to general physics and Leibniz developed much of the notation used in calculus today. The basic insights that both Newton and Leibniz provided were the laws of differentiation and integration, second and higher derivatives, and the notion of an approximating polynomial serial.

When Newton and Leibniz starting time published their results, there was nifty controversy over which mathematician (and therefore which country) deserved credit. Newton derived his results get-go (subsequently to be published in his Method of Fluxions), simply Leibniz published his "Nova Methodus pro Maximis et Minimis" first. Newton claimed Leibniz stole ideas from his unpublished notes, which Newton had shared with a few members of the Purple Gild. This controversy divided English-speaking mathematicians from continental European mathematicians for many years, to the detriment of English mathematics.[29] A careful examination of the papers of Leibniz and Newton shows that they arrived at their results independently, with Leibniz starting first with integration and Newton with differentiation. It is Leibniz, even so, who gave the new discipline its name. Newton called his calculus "the scientific discipline of fluxions", a term that endured in English schools into the 19th century.[30] : 100 The start complete treatise on calculus to be written in English language and use the Leibniz note was non published until 1815.[31]

Since the fourth dimension of Leibniz and Newton, many mathematicians have contributed to the continuing development of calculus. One of the first and virtually complete works on both infinitesimal and integral calculus was written in 1748 by Maria Gaetana Agnesi.[32] [33]

Foundations

In calculus, foundations refers to the rigorous development of the bailiwick from axioms and definitions. In early calculus the use of infinitesimal quantities was thought unrigorous, and was fiercely criticized by a number of authors, most notably Michel Rolle and Bishop Berkeley. Berkeley famously described infinitesimals as the ghosts of departed quantities in his book The Analyst in 1734. Working out a rigorous foundation for calculus occupied mathematicians for much of the century following Newton and Leibniz, and is still to some extent an active area of research today.[34]

Several mathematicians, including Maclaurin, tried to prove the soundness of using infinitesimals, but it would not be until 150 years subsequently when, due to the piece of work of Cauchy and Weierstrass, a way was finally found to avoid mere "notions" of infinitely small quantities.[35] The foundations of differential and integral calculus had been laid. In Cauchy's Cours d'Analyse, nosotros observe a wide range of foundational approaches, including a definition of continuity in terms of infinitesimals, and a (somewhat imprecise) prototype of an (ε, δ)-definition of limit in the definition of differentiation.[36] In his piece of work Weierstrass formalized the concept of limit and eliminated infinitesimals (although his definition can really validate nilsquare infinitesimals). Following the work of Weierstrass, it eventually became common to base of operations calculus on limits instead of minute quantities, though the subject is nevertheless occasionally called "infinitesimal calculus". Bernhard Riemann used these ideas to give a precise definition of the integral.[37] It was also during this menstruation that the ideas of calculus were generalized to the complex plane with the development of complex analysis.[38]

In modern mathematics, the foundations of calculus are included in the field of existent analysis, which contains full definitions and proofs of the theorems of calculus. The reach of calculus has also been greatly extended. Henri Lebesgue invented mensurate theory, based on before developments by Émile Borel, and used information technology to define integrals of all just the most pathological functions.[39] Laurent Schwartz introduced distributions, which can be used to accept the derivative of whatsoever office whatever.[40]

Limits are not the just rigorous approach to the foundation of calculus. Another way is to use Abraham Robinson'due south non-standard assay. Robinson's approach, adult in the 1960s, uses technical machinery from mathematical logic to augment the existent number system with infinitesimal and infinite numbers, as in the original Newton-Leibniz conception. The resulting numbers are chosen hyperreal numbers, and they can exist used to give a Leibniz-like development of the usual rules of calculus.[41] There is also smoothen minute assay, which differs from non-standard analysis in that it mandates neglecting college-ability infinitesimals during derivations.[34]

Significance

While many of the ideas of calculus had been developed earlier in Greece, Prc, India, Iraq, Persia, and Japan, the use of calculus began in Europe, during the 17th century, when Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz built on the work of earlier mathematicians to introduce its basic principles.[xi] [26] [42] The development of calculus was built on earlier concepts of instantaneous motion and area underneath curves.

Applications of differential calculus include computations involving velocity and acceleration, the gradient of a curve, and optimization. Applications of integral calculus include computations involving area, volume, arc length, middle of mass, work, and pressure. More avant-garde applications include ability serial and Fourier serial.

Calculus is besides used to gain a more than precise understanding of the nature of infinite, fourth dimension, and motion. For centuries, mathematicians and philosophers wrestled with paradoxes involving division by zero or sums of infinitely many numbers. These questions arise in the study of movement and surface area. The ancient Greek philosopher Zeno of Elea gave several famous examples of such paradoxes. Calculus provides tools, especially the limit and the space serial, that resolve the paradoxes.[43]

Principles

Limits and infinitesimals

Calculus is usually developed past working with very small quantities. Historically, the commencement method of doing so was by infinitesimals. These are objects which can exist treated like real numbers but which are, in some sense, "infinitely minor". For example, an infinitesimal number could be greater than 0, but less than whatever number in the sequence 1, i/2, 1/3, ... and thus less than any positive real number. From this point of view, calculus is a collection of techniques for manipulating infinitesimals. The symbols and were taken to exist infinitesimal, and the derivative was simply their ratio.[34]

The infinitesimal approach brutal out of favor in the 19th century considering it was hard to make the notion of an infinitesimal precise. In the late 19th century, infinitesimals were replaced within academia by the epsilon, delta approach to limits. Limits describe the behavior of a part at a certain input in terms of its values at nearby inputs. They capture pocket-sized-scale behavior in the context of the existent number system. In this handling, calculus is a collection of techniques for manipulating certain limits. Infinitesimals go replaced past very small numbers, and the infinitely small behavior of the function is found past taking the limiting behavior for smaller and smaller numbers. Limits were thought to provide a more than rigorous foundation for calculus, and for this reason they became the standard approach during the 20th century. However, the minute concept was revived in the 20th century with the introduction of not-standard analysis and smooth infinitesimal analysis, which provided solid foundations for the manipulation of infinitesimals.[34]

Differential calculus

Tangent line at (x 0, f(x 0)). The derivative f′(x) of a bend at a point is the gradient (rise over run) of the line tangent to that curve at that indicate.

Differential calculus is the report of the definition, properties, and applications of the derivative of a part. The process of finding the derivative is called differentiation. Given a function and a point in the domain, the derivative at that betoken is a way of encoding the small-scale-calibration behavior of the function about that point. Past finding the derivative of a role at every point in its domain, it is possible to produce a new part, called the derivative function or just the derivative of the original function. In formal terms, the derivative is a linear operator which takes a function as its input and produces a 2d office as its output. This is more than abstruse than many of the processes studied in elementary algebra, where functions usually input a number and output some other number. For example, if the doubling function is given the input 3, and then information technology outputs half-dozen, and if the squaring part is given the input three, then it outputs 9. The derivative, however, can take the squaring function as an input. This means that the derivative takes all the data of the squaring function—such equally that two is sent to four, three is sent to nine, 4 is sent to sixteen, and so on—and uses this information to produce some other function. The role produced past differentiating the squaring office turns out to be the doubling function.[44] : 32

In more explicit terms the "doubling role" may be denoted by g(x) = 210 and the "squaring part" by f(x) = x 2 . The "derivative" now takes the part f(x), defined past the expression " x 2 ", as an input, that is all the information—such as that two is sent to four, iii is sent to nine, four is sent to sixteen, and then on—and uses this information to output another function, the function g(x) = 2x , every bit will turn out.

In Lagrange'due south notation, the symbol for a derivative is an apostrophe-like marking called a prime. Thus, the derivative of a part called f is denoted by f′ , pronounced "f prime". For case, if f(x) = x ii is the squaring office, and then f′(x) = 2x is its derivative (the doubling function k from higher up).

If the input of the function represents time, then the derivative represents change with respect to time. For example, if f is a function that takes a fourth dimension as input and gives the position of a ball at that fourth dimension as output, then the derivative of f is how the position is irresolute in fourth dimension, that is, information technology is the velocity of the ball.[44] : 18–20

If a function is linear (that is, if the graph of the office is a straight line), and so the function can be written as y = mx + b , where x is the independent variable, y is the dependent variable, b is the y-intercept, and:

This gives an verbal value for the slope of a straight line. If the graph of the function is not a straight line, nevertheless, and so the change in y divided by the alter in x varies. Derivatives requite an exact pregnant to the notion of change in output with respect to alter in input. To exist physical, permit f exist a function, and set up a bespeak a in the domain of f . (a, f(a)) is a bespeak on the graph of the role. If h is a number close to zero, and so a + h is a number shut to a . Therefore, (a + h, f(a + h)) is close to (a, f(a)). The slope between these two points is

This expression is called a difference quotient. A line through 2 points on a curve is called a secant line, and then m is the slope of the secant line between (a, f(a)) and (a + h, f(a + h)). The secant line is only an approximation to the behavior of the office at the bespeak a because it does non business relationship for what happens between a and a + h . It is not possible to find the behavior at a by setting h to zero because this would crave dividing past zero, which is undefined. The derivative is defined past taking the limit as h tends to zilch, meaning that it considers the behavior of f for all pocket-sized values of h and extracts a consistent value for the case when h equals cipher:

Geometrically, the derivative is the slope of the tangent line to the graph of f at a . The tangent line is a limit of secant lines just every bit the derivative is a limit of difference quotients. For this reason, the derivative is sometimes chosen the slope of the function f .

Here is a item example, the derivative of the squaring function at the input three. Allow f(x) = x 2 be the squaring part.

The derivative f′(ten) of a curve at a bespeak is the slope of the line tangent to that curve at that point. This slope is determined by considering the limiting value of the slopes of secant lines. Here the function involved (drawn in red) is f(x) = 10 3 − x . The tangent line (in green) which passes through the betoken (−3/2, −15/8) has a slope of 23/iv. Notation that the vertical and horizontal scales in this image are unlike.

The slope of the tangent line to the squaring role at the bespeak (3, ix) is half dozen, that is to say, it is going upwardly six times as fast every bit it is going to the right. The limit procedure just described can be performed for any point in the domain of the squaring function. This defines the derivative office of the squaring function or just the derivative of the squaring function for short. A computation like to the one above shows that the derivative of the squaring function is the doubling part.

Leibniz notation

A mutual notation, introduced by Leibniz, for the derivative in the example above is

In an arroyo based on limits, the symbol dy / dx is to be interpreted non equally the quotient of two numbers but as a shorthand for the limit computed in a higher place. Leibniz, however, did intend it to represent the quotient of ii infinitesimally minor numbers, dy being the infinitesimally small modify in y caused by an infinitesimally small alter dx practical to x . We can also recollect of d / dx equally a differentiation operator, which takes a part equally an input and gives another part, the derivative, every bit the output. For example:

In this usage, the dx in the denominator is read as "with respect to ten ". Another example of correct note could be:

Fifty-fifty when calculus is developed using limits rather than infinitesimals, it is common to manipulate symbols like dx and dy as if they were existent numbers; although it is possible to avert such manipulations, they are sometimes notationally convenient in expressing operations such equally the full derivative.

Integral calculus

Integral calculus is the written report of the definitions, properties, and applications of ii related concepts, the indefinite integral and the definite integral. The process of finding the value of an integral is chosen integration. In technical language, integral calculus studies ii related linear operators.

The indefinite integral, also known as the antiderivative, is the inverse operation to the derivative. F is an indefinite integral of f when f is a derivative of F . (This employ of lower- and upper-case letters for a function and its indefinite integral is mutual in calculus.)

The definite integral inputs a role and outputs a number, which gives the algebraic sum of areas between the graph of the input and the x-axis. The technical definition of the definite integral involves the limit of a sum of areas of rectangles, called a Riemann sum.[45] : 282

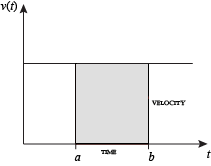

A motivating example is the distance traveled in a given time. If the speed is constant, only multiplication is needed:

Only if the speed changes, a more than powerful method of finding the distance is necessary. I such method is to approximate the distance traveled by breaking up the time into many short intervals of time, then multiplying the time elapsed in each interval past one of the speeds in that interval, and and then taking the sum (a Riemann sum) of the approximate altitude traveled in each interval. The basic idea is that if only a short time elapses, then the speed will stay more than or less the aforementioned. Notwithstanding, a Riemann sum only gives an approximation of the distance traveled. Nosotros must accept the limit of all such Riemann sums to observe the verbal altitude traveled.

Integration tin can exist thought of as measuring the area under a curve, divers by f(x), betwixt two points (hither a and b ).

When velocity is constant, the total distance traveled over the given fourth dimension interval tin be computed by multiplying velocity and time. For example, travelling a steady l mph for 3 hours results in a full distance of 150 miles. In the diagram on the left, when constant velocity and fourth dimension are graphed, these two values class a rectangle with tiptop equal to the velocity and width equal to the time elapsed. Therefore, the production of velocity and fourth dimension also calculates the rectangular area under the (constant) velocity curve. This connexion betwixt the area nether a curve and distance traveled can be extended to any irregularly shaped region exhibiting a fluctuating velocity over a given time period. If f(ten) in the diagram on the right represents speed as it varies over fourth dimension, the distance traveled (between the times represented by a and b ) is the area of the shaded region s .

To gauge that expanse, an intuitive method would be to split upwardly the distance betwixt a and b into a number of equal segments, the length of each segment represented by the symbol Δx . For each modest segment, we can cull ane value of the function f(ten). Call that value h . And then the area of the rectangle with base of operations Δx and peak h gives the altitude (time Δx multiplied by speed h ) traveled in that segment. Associated with each segment is the average value of the role above it, f(x) = h . The sum of all such rectangles gives an approximation of the area between the axis and the curve, which is an approximation of the total altitude traveled. A smaller value for Δx will give more rectangles and in nearly cases a better approximation, merely for an exact answer nosotros need to accept a limit as Δ10 approaches zero.

The symbol of integration is , an elongated S (the S stands for "sum"). The definite integral is written every bit:

and is read "the integral from a to b of f-of-x with respect to x." The Leibniz annotation dx is intended to suggest dividing the area under the bend into an infinite number of rectangles, and so that their width Δx becomes the infinitesimally small dx .[44] : 44 In a conception of the calculus based on limits, the notation

is to be understood as an operator that takes a office as an input and gives a number, the area, equally an output. The terminating differential, dx , is not a number, and is not being multiplied by f(10), although, serving as a reminder of the Δx limit definition, information technology can be treated as such in symbolic manipulations of the integral. Formally, the differential indicates the variable over which the office is integrated and serves every bit a closing bracket for the integration operator.

The indefinite integral, or antiderivative, is written:

Functions differing by only a constant have the same derivative, and it can be shown that the antiderivative of a given function is actually a family of functions differing only past a constant.[45] : 326 Since the derivative of the function y = x two + C , where C is any constant, is y′ = two10 , the antiderivative of the latter is given by:

The unspecified constant C present in the indefinite integral or antiderivative is known equally the constant of integration.

Fundamental theorem

The central theorem of calculus states that differentiation and integration are inverse operations.[45] : 290 More precisely, information technology relates the values of antiderivatives to definite integrals. Considering information technology is usually easier to compute an antiderivative than to apply the definition of a definite integral, the fundamental theorem of calculus provides a practical way of computing definite integrals. Information technology can also be interpreted as a precise argument of the fact that differentiation is the inverse of integration.

The fundamental theorem of calculus states: If a function f is continuous on the interval [a, b] and if F is a function whose derivative is f on the interval (a, b), and so

Furthermore, for every x in the interval (a, b),

This realization, made by both Newton and Leibniz, was key to the proliferation of analytic results later on their work became known. (The extent to which Newton and Leibniz were influenced by immediate predecessors, and particularly what Leibniz may have learned from the work of Isaac Barrow, is difficult to decide thanks to the priority dispute between them.[46]) The fundamental theorem provides an algebraic method of calculating many definite integrals—without performing limit processes—by finding formulae for antiderivatives. It is also a image solution of a differential equation. Differential equations relate an unknown function to its derivatives, and are ubiquitous in the sciences.

Applications

Calculus is used in every branch of the physical sciences,[47] : 1 actuarial scientific discipline, computer science, statistics, technology, economics, concern, medicine, demography, and in other fields wherever a problem can be mathematically modeled and an optimal solution is desired. It allows ane to become from (non-constant) rates of alter to the total change or vice versa, and many times in studying a trouble we know i and are trying to find the other.[48] Calculus tin be used in conjunction with other mathematical disciplines. For example, information technology can be used with linear algebra to observe the "all-time fit" linear approximation for a set up of points in a domain. Or, it tin can be used in probability theory to make up one's mind the expectation value of a continuous random variable given a probability density function.[49] : 37 In analytic geometry, the study of graphs of functions, calculus is used to find loftier points and depression points (maxima and minima), gradient, concavity and inflection points. Calculus is as well used to find approximate solutions to equations; in practice it is the standard way to solve differential equations and do root finding in most applications. Examples are methods such every bit Newton'southward method, stock-still point iteration, and linear approximation. For case, spacecraft use a variation of the Euler method to guess curved courses within zero gravity environments.

Physics makes particular employ of calculus; all concepts in classical mechanics and electromagnetism are related through calculus. The mass of an object of known density, the moment of inertia of objects, and the potential energies due to gravitational and electromagnetic forces tin can all be found by the use of calculus. An example of the use of calculus in mechanics is Newton's second law of motion, which states that the derivative of an object's momentum with respect to fourth dimension equals the cyberspace force upon information technology. Alternatively, Newton'south 2nd law tin be expressed by saying that the net force is equal to the object's mass times its acceleration, which is the time derivative of velocity and thus the second time derivative of spatial position. Starting from knowing how an object is accelerating, we employ calculus to derive its path.[50]

Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism and Einstein's theory of general relativity are too expressed in the linguistic communication of differential calculus.[51] [52] : 52–55 Chemistry also uses calculus in determining reaction rates[53] : 599 and in studying radioactive disuse.[53] : 814 In biology, population dynamics starts with reproduction and expiry rates to model population changes.[54] [55] : 631

Dark-green's theorem, which gives the relationship between a line integral around a simple airtight curve C and a double integral over the plane region D bounded by C, is applied in an instrument known equally a planimeter, which is used to summate the area of a flat surface on a drawing.[56] For instance, it can be used to calculate the amount of area taken up by an irregularly shaped blossom bed or pond pool when designing the layout of a piece of property.

In the realm of medicine, calculus can be used to notice the optimal branching angle of a blood vessel and then as to maximize flow.[57] Calculus can be applied to sympathise how rapidly a drug is eliminated from a torso or how chop-chop a cancerous neoplasm grows.[58]

In economics, calculus allows for the determination of maximal profit by providing a way to easily summate both marginal cost and marginal revenue.[59] : 387

Varieties

Over the years, many reformulations of calculus take been investigated for different purposes.

Non-standard calculus

Imprecise calculations with infinitesimals were widely replaced with the rigorous (ε, δ)-definition of limit starting in the 1870s. Meanwhile, calculations with infinitesimals persisted and often led to correct results. This led Abraham Robinson to investigate if it were possible to develop a number system with infinitesimal quantities over which the theorems of calculus were still valid. In 1960, building upon the work of Edwin Hewitt and Jerzy Łoś, he succeeded in developing non-standard analysis. The theory of non-standard analysis is rich enough to be applied in many branches of mathematics. As such, books and manufactures dedicated solely to the traditional theorems of calculus ofttimes go by the championship not-standard calculus.

Smooth infinitesimal analysis

This is another reformulation of the calculus in terms of infinitesimals. Based on the ideas of F. W. Lawvere and employing the methods of category theory, information technology views all functions equally being continuous and incapable of being expressed in terms of discrete entities. One aspect of this formulation is that the constabulary of excluded middle does non hold in this conception.[34]

Constructive analysis

Constructive mathematics is a branch of mathematics that insists that proofs of the existence of a number, function, or other mathematical object should requite a construction of the object. As such effective mathematics besides rejects the law of excluded middle. Reformulations of calculus in a constructive framework are generally part of the field of study of constructive analysis.[34]

Come across also

Lists

- Glossary of calculus

- List of calculus topics

- List of derivatives and integrals in alternative calculi

- List of differentiation identities

- Publications in calculus

- Table of integrals

- Calculus with polynomials

- Complex analysis

- Differential geometry

- Uncomplicated Calculus: An Infinitesimal Arroyo

- Discrete calculus

- Integral equation

- Multivariable calculus

- Precalculus (mathematical didactics)

- Product integral

- Stochastic calculus

References

- ^ DeBaggis, Henry F.; Miller, Kenneth Due south. (1966). Foundations of the Calculus. Philadelphia: Saunders. OCLC 527896.

- ^ Boyer, Carl B. (1959). The History of the Calculus and its Conceptual Development . New York: Dover. OCLC 643872.

- ^ Bardi, Jason Socrates (2006). The Calculus Wars : Newton, Leibniz, and the Greatest Mathematical Clash of All Time. New York: Thunder's Rima oris Printing. ISBN1-56025-706-vii.

- ^ Hoffmann, Laurence D.; Bradley, Gerald 50. (2004). Calculus for Business, Economics, and the Social and Life Sciences (8th ed.). Boston: McGraw Loma. ISBN0-07-242432-X.

- ^ Run across, for example:

- "history - Were metered taxis busy roaming Purple Rome?". Skeptics Stack Exchange. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- Cousineau, Phil (xv March 2010). Wordcatcher: An Odyssey into the Earth of Weird and Wonderful Words. Simon and Schuster. p. 58. ISBN978-1-57344-550-4. OCLC 811492876.

- ^ "calculus". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Kline, Morris (16 August 1990). Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Mod Times: Book 1. Oxford University Printing. pp. 15–21. ISBN978-0-nineteen-506135-ii.

- ^ Imhausen, Annette (2016). Mathematics in Ancient Egypt: A Contextual History. Princeton University Press. p. 112. ISBN978-1-4008-7430-ix. OCLC 934433864.

- ^ Run across, for example:

- Powers, J. (2020). ""Did Archimedes do calculus?"" (PDF). Mathematical Association of America.

- Jullien, Vincent (2015). "Archimedes and Indivisibles". Seventeenth-Century Indivisibles Revisited. Science Networks. Historical Studies. Vol. 49. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 451–457. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-00131-9_18. ISBN978-3-319-00130-2.

- Plummer, Brad (ix Baronial 2006). "Modern Ten-ray engineering reveals Archimedes' math theory nether forged painting". Stanford University . Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- Archimedes (2004). The Works of Archimedes, Volume 1: The Two Books On the Sphere and the Cylinder. Translated past Netz, Reviel. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-66160-seven.

- Greyness, Shirley; Waldman, Cye H. (20 October 2018). "Archimedes Redux: Center of Mass Applications from The Method". The College Mathematics Journal. 49 (v): 346–352. doi:10.1080/07468342.2018.1524647. ISSN 0746-8342. S2CID 125411353.

- ^ Dun, Liu; Fan, Dainian; Cohen, Robert Sonné (1966). A comparison of Archimdes' and Liu Hui's studies of circles. Chinese studies in the history and philosophy of science and engineering. Vol. 130. Springer. p. 279. ISBN978-0-7923-3463-seven. ,pp. 279ff

- ^ a b Dainian Fan; R. S. Cohen (1996). Chinese studies in the history and philosophy of scientific discipline and technology. Dordrecht: Kluwer Bookish Publishers. ISBN0-7923-3463-9. OCLC 32272485.

- ^ Katz, Victor J. (2008). A history of mathematics (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley. p. 203. ISBN978-0-321-38700-4.

- ^ Zill, Dennis 1000.; Wright, Scott; Wright, Warren S. (2009). Calculus: Early Transcendentals (iii ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. xxvii. ISBN978-0-7637-5995-7. Extract of page 27

- ^ a b Katz, Victor J. (June 1995). "Ideas of Calculus in Islam and Republic of india". Mathematics Mag. 68 (3): 163–174. doi:10.1080/0025570X.1995.11996307. ISSN 0025-570X. JSTOR 2691411.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "An overview of Indian mathematics", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, Academy of St Andrews

- ^ Plofker, Kim (2009). Mathematics in Republic of india. Princeton: Princeton University Printing. ISBN978-1-4008-3407-5. OCLC 650305544.

- ^ von Neumann, J. (1947). "The Mathematician". In Heywood, R. B. (ed.). The Works of the Listen. University of Chicago Press. pp. 180–196. Reprinted in Bródy, F.; Vámos, T., eds. (1995). The Neumann Compendium. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. pp. 618–626. ISBN981-02-2201-seven.

- ^ "Johannes Kepler: His Life, His Laws and Times". NASA. 24 September 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Printing. p. 537.

- ^ Weil, André (1984). Number theory: An approach through History from Hammurapi to Legendre. Boston: Birkhauser Boston. p. 28. ISBN0-8176-4565-9.

- ^ Hollingdale, Stuart (1991). "Review of Earlier Newton: The Life and Times of Isaac Barrow". Notes and Records of the Royal Social club of London. 45 (2): 277–279. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1991.0027. ISSN 0035-9149. JSTOR 531707. S2CID 165043307.

The near interesting to us are Lectures X-XII, in which Barrow comes close to providing a geometrical demonstration of the fundamental theorem of the calculus... He did not realize, however, the full significance of his results, and his rejection of algebra means that his work must remain a piece of mid-17th century geometrical assay of mainly historic interest.

- ^ Bressoud, David M. (2011). "Historical Reflections on Teaching the Fundamental Theorem of Integral Calculus". The American Mathematical Monthly. 118 (ii): 99. doi:10.4169/amer.math.monthly.118.02.099. S2CID 21473035.

- ^ Blank, Brian Due east.; Krantz, Steven George (2006). Calculus: Single Variable, Book one (Illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 248. ISBN978-i-931914-59-eight.

- ^ Ferraro, Giovanni (2007). The Rise and Development of the Theory of Series upwards to the Early 1820s (Illustrated ed.). Springer Scientific discipline & Business concern Media. p. 87. ISBN978-0-387-73468-2.

- ^ Guicciardini, Niccolò (2005). "Isaac Newton, Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica, starting time edition (1687)". Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics 1640-1940. Elsevier. pp. 59–87. doi:10.1016/b978-044450871-3/50086-three. ISBN978-0-444-50871-3.

[Newton] immediately realised that quadrature problems (the inverse problems) could be tackled via infinite serial: every bit we would say nowadays, by expanding the integrand in power series and integrating term-wise.

- ^ a b Grattan-Guinness, I., ed. (2005). Landmark writings in Western mathematics 1640-1940. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN0-444-50871-six. OCLC 60416766.

- ^ Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm (2008). The Early Mathematical Manuscripts of Leibniz. Cosimo, Inc. p. 228. ISBN978-1-605-20533-five.

- ^ Mazur, Joseph (2014). Enlightening Symbols / A Short History of Mathematical Notation and Its Subconscious Powers. Princeton Academy Press. p. 166. ISBN978-0-691-17337-5.

Leibniz understood symbols, their conceptual powers also every bit their limitations. He would spend years experimenting with some—adjusting, rejecting, and corresponding with everyone he knew, consulting with equally many of the leading mathematicians of the time who were sympathetic to his fastidiousness.

- ^ Schrader, Dorothy V. (1962). "The Newton-Leibniz controversy concerning the discovery of the calculus". The Mathematics Teacher. 55 (5): 385–396. doi:10.5951/MT.55.5.0385. ISSN 0025-5769. JSTOR 27956626.

- ^ Stedall, Jacqueline (2012). The History of Mathematics: A Very Brusk Introduction. Oxford Academy Press. ISBN978-0-191-63396-6.

- ^ Stenhouse, Brigitte (May 2020). "Mary Somerville's early contributions to the circulation of differential calculus". Historia Mathematica. 51: one–25. doi:x.1016/j.hm.2019.12.001. S2CID 214472568.

- ^ Allaire, Patricia R. (2007). Foreword. A Biography of Maria Gaetana Agnesi, an Eighteenth-century Adult female Mathematician. By Cupillari, Antonella. Edwin Mellen Press. p. iii. ISBN978-0-7734-5226-8.

- ^ Unlu, Elif (Apr 1995). "Maria Gaetana Agnesi". Agnes Scott College.

- ^ a b c d e f Bell, John L. (half-dozen September 2013). "Continuity and Infinitesimals". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Retrieved xx February 2022.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (1946). History of Western Philosophy. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. p. 857.

The great mathematicians of the seventeenth century were optimistic and anxious for quick results; consequently they left the foundations of analytical geometry and the minute calculus insecure. Leibniz believed in actual infinitesimals, merely although this conventionalities suited his metaphysics it had no sound basis in mathematics. Weierstrass, soon later the middle of the nineteenth century, showed how to establish the calculus without infinitesimals, and thus at terminal made it logically secure. Next came Georg Cantor, who developed the theory of continuity and infinite number. "Continuity" had been, until he divers it, a vague discussion, convenient for philosophers similar Hegel, who wished to introduce metaphysical muddles into mathematics. Cantor gave a precise significance to the word, and showed that continuity, as he defined it, was the concept needed by mathematicians and physicists. Past this means a peachy deal of mysticism, such equally that of Bergson, was rendered antiquated.

- ^ Grabiner, Judith V. (1981). The Origins of Cauchy'due south Rigorous Calculus . Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN978-0-387-90527-three.

- ^ Archibald, Tom (2008). "The Development of Rigor in Mathematical Analysis". In Gowers, Timothy; Barrow-Green, June; Leader, Imre (eds.). The Princeton Companion to Mathematics. Princeton Academy Press. pp. 117–129. ISBN978-0-691-11880-two. OCLC 682200048.

- ^ Rice, Adrian (2008). "A Chronology of Mathematical Events". In Gowers, Timothy; Barrow-Light-green, June; Leader, Imre (eds.). The Princeton Companion to Mathematics. Princeton Academy Press. pp. 1010–1014. ISBN978-0-691-11880-ii. OCLC 682200048.

- ^ Siegmund-Schultze, Reinhard (2008). "Henri Lebesgue". In Gowers, Timothy; Barrow-Dark-green, June; Leader, Imre (eds.). The Princeton Companion to Mathematics. Princeton University Press. pp. 796–797. ISBN978-0-691-11880-2. OCLC 682200048.

- ^ Barany, Michael J.; Paumier, Anne-Sandrine; Lützen, Jesper (November 2017). "From Nancy to Copenhagen to the World: The internationalization of Laurent Schwartz and his theory of distributions". Historia Mathematica. 44 (4): 367–394. doi:10.1016/j.hm.2017.04.002.

- ^ Daubin, Joseph W. (2008). "Abraham Robinson". In Gowers, Timothy; Barrow-Green, June; Leader, Imre (eds.). The Princeton Companion to Mathematics. Princeton Academy Press. pp. 822–823. ISBN978-0-691-11880-two. OCLC 682200048.

- ^ Kline, Morris (1990). Mathematical thought from ancient to modern times. 5. 3. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-977048-ix. OCLC 726764443.

- ^ Cheng, Eugenia (2017). Beyond Infinity: An Expedition to the Outer Limits of Mathematics. Basic Books. pp. 206–210. ISBN978-1-541-64413-seven. OCLC 1003309980.

- ^ a b c Frautschi, Steven C.; Olenick, Richard P.; Apostol, Tom M.; Goodstein, David L. (2007). The Mechanical Universe: Mechanics and Heat (Advanced ed.). Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-71590-4. OCLC 227002144.

- ^ a b c Hughes-Hallett, Deborah; McCallum, William G.; Gleason, Andrew Chiliad.; et al. (2013). Calculus: Single and Multivariable (6th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN978-0-470-88861-2. OCLC 794034942.

- ^ See, for example:

- Mahoney, Michael Due south. (1990). "Barrow'south mathematics: Betwixt ancients and moderns". In Feingold, M. (ed.). Before Newton. Cambridge University Press. pp. 179–249. ISBN978-0-521-06385-2.

- Feingold, One thousand. (June 1993). "Newton, Leibniz, and Barrow As well: An Try at a Reinterpretation". Isis. 84 (ii): 310–338. Bibcode:1993Isis...84..310F. doi:10.1086/356464. ISSN 0021-1753. S2CID 144019197.

- Probst, Siegmund (2015). "Leibniz as Reader and 2nd Inventor: The Cases of Barrow and Mengoli". In Goethe, Norma B.; Beeley, Philip; Rabouin, David (eds.). G.West. Leibniz, Interrelations Between Mathematics and Philosophy. Archimedes: New Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Applied science. Vol. 41. Springer. pp. 111–134. ISBN978-9-401-79663-vii.

- ^ Businesswoman, Margaret Due east. (1969). The origins of the minute calculus (1st ed.). Oxford. ISBN978-one-483-28092-9. OCLC 892067655.

- ^ Hu, Zhiying (14 April 2021). "The Application and Value of Calculus in Daily Life". 2021 2nd Asia-Pacific Conference on Image Processing, Electronics and Computers. Ipec2021. Dalian China: ACM: 562–564. doi:10.1145/3452446.3452583. ISBN978-1-4503-8981-v. S2CID 233384462.

- ^ Kardar, Mehran (2007). Statistical Physics of Particles. Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN978-0-521-87342-0. OCLC 860391091.

- ^ Garber, Elizabeth (2001). The language of physics : the calculus and the development of theoretical physics in Europe, 1750-1914. Springer Science+Business organization Media. ISBN978-one-4612-7272-4. OCLC 921230825.

- ^ Hall, Graham (2008). "Maxwell'southward Electromagnetic Theory and Special Relativity". Philosophical Transactions: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering science Sciences. 366 (1871): 1849–1860. Bibcode:2008RSPTA.366.1849H. doi:10.1098/rsta.2007.2192. ISSN 1364-503X. JSTOR 25190792. PMID 18218598. S2CID 502776.

- ^ Gbur, Greg (2011). Mathematical Methods for Optical Physics and Applied science. Cambridge, U.G.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-511-91510-ix. OCLC 704518582.

- ^ a b Atkins, Peter W.; Jones, Loretta (2010). Chemical principles : the quest for insight (5th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. ISBN978-1-4292-1955-half dozen. OCLC 501943698.

- ^ Murray, J. D. (2002). Mathematical biology. I, Introduction (tertiary ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN0-387-22437-viii. OCLC 53165394.

- ^ Neuhauser, Claudia (2011). Calculus for biological science and medicine (tertiary ed.). Boston: Prentice Hall. ISBN978-0-321-64468-viii. OCLC 426065941.

- ^ Gatterdam, R. W. (1981). "The planimeter as an example of Green'southward theorem". The American Mathematical Monthly. 88 (nine): 701–704. doi:x.2307/2320679. JSTOR 2320679.

- ^ Adam, John A. (June 2011). "Claret Vessel Branching: Beyond the Standard Calculus Problem". Mathematics Magazine. 84 (3): 196–207. doi:10.4169/math.mag.84.3.196. ISSN 0025-570X. S2CID 8259705.

- ^ Mackenzie, Dana (2004). "Mathematical Modeling and Cancer" (PDF). SIAM News. 37 (1).

- ^ Perloff, Jeffrey M. (2018). Microeconomics : Theory and Applications with Calculus (4th global ed.). Harlow, United kingdom. ISBN978-i-292-15446-6. OCLC 1064041906.

Further reading

- Adams, Robert A. (1999). Calculus: A consummate grade. ISBN978-0-201-39607-2.

- Albers, Donald J.; Anderson, Richard D.; Loftsgaarden, Don O., eds. (1986). Undergraduate Programs in the Mathematics and Estimator Sciences: The 1985–1986 Survey. Mathematical Association of America.

- Anton, Howard; Bivens, Irl; Davis, Stephen (2002). Calculus. John Willey and Sons Pte. Ltd. ISBN978-81-265-1259-i.

- Apostol, Tom 1000. (1967). Calculus, Volume ane, I-Variable Calculus with an Introduction to Linear Algebra. Wiley. ISBN978-0-471-00005-1.

- Apostol, Tom K. (1969). Calculus, Volume ii, Multi-Variable Calculus and Linear Algebra with Applications. Wiley. ISBN978-0-471-00007-5.

- Bell, John Lane (1998). A Primer of Infinitesimal Assay. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-62401-5. Uses constructed differential geometry and nilpotent infinitesimals.

- Boelkins, Yard. (2012). Active Calculus: a gratis, open text (PDF). Archived from the original on xxx May 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- Boyer, Carl Benjamin (1959) [1949]. The History of the Calculus and its Conceptual Development (Dover ed.). Hafner. ISBN0-486-60509-4.

- Cajori, Florian (September 1923). "The History of Notations of the Calculus". Annals of Mathematics. 2nd Serial. 25 (1): 1–46. doi:10.2307/1967725. hdl:2027/mdp.39015017345896. JSTOR 1967725.

- Courant, Richard. Introduction to calculus and analysis 1. ISBN978-3-540-65058-4.

- Gonick, Larry (2012). The Drawing Guide to Calculus. William Morrow. ISBN978-0-061-68909-3. OCLC 932781617.

- Keisler, H.J. (2000). Elementary Calculus: An Approach Using Infinitesimals. Retrieved 29 Baronial 2010 from http://www.math.wisc.edu/~keisler/calc.html

- Landau, Edmund (2001). Differential and Integral Calculus. American Mathematical Society. ISBN0-8218-2830-4.

- Lebedev, Leonid P.; Deject, Michael J. (2004). "The Tools of Calculus". Approximating Perfection: a Mathematician's Journeying into the World of Mechanics. Princeton University Press.

- Larson, Ron; Edwards, Bruce H. (2010). Calculus (9th ed.). Brooks Cole Cengage Learning. ISBN978-0-547-16702-ii.

- McQuarrie, Donald A. (2003). Mathematical Methods for Scientists and Engineers. University Scientific discipline Books. ISBN978-1-891389-24-5.

- Pickover, Cliff (2003). Calculus and Pizza: A Math Cookbook for the Hungry Mind. ISBN978-0-471-26987-8.

- Salas, Saturnino Fifty.; Hille, Einar; Etgen, Garret J. (2007). Calculus: One and Several Variables (tenth ed.). Wiley. ISBN978-0-471-69804-3.

- Spivak, Michael (September 1994). Calculus. Publish or Perish publishing. ISBN978-0-914098-89-8.

- Steen, Lynn Arthur, ed. (1988). Calculus for a New Century; A Pump, Non a Filter. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN0-88385-058-3.

- Stewart, James (2012). Calculus: Early Transcendentals (seventh ed.). Brooks Cole Cengage Learning. ISBN978-0-538-49790-9.

- Thomas, George Brinton; Finney, Ross 50.; Weir, Maurice D. (1996). Calculus and Analytic Geometry, Part 1. Addison Wesley. ISBN978-0-201-53174-9.

- Thomas, George B.; Weir, Maurice D.; Hass, Joel; Giordano, Frank R. (2008). Calculus (11th ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN978-0-321-48987-6.

- Thompson, Silvanus P.; Gardner, Martin (1998). Calculus Made Like shooting fish in a barrel. ISBN978-0-312-18548-0.

External links

- "Calculus", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Printing, 2001 [1994]

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Calculus". MathWorld.

- Topics on Calculus at PlanetMath.

- Calculus Made Easy (1914) by Silvanus P. Thompson Full text in PDF

- Calculus on In Our Time at the BBC

- Calculus.org: The Calculus page at University of California, Davis – contains resource and links to other sites

- Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics: Calculus & Analysis

- The Role of Calculus in College Mathematics from ERICDigests.org

- OpenCourseWare Calculus from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Minute Calculus – an commodity on its historical evolution, in Encyclopedia of Mathematics, ed. Michiel Hazewinkel.

- Daniel Kleitman, MIT. "Calculus for Beginners and Artists".

- Calculus training materials at imomath.com

- (in English and Standard arabic) The Circuit of Calculus, 1772

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calculus

0 Response to "Review of Limtis Solve Each of the 17 Problems on Limits"

Post a Comment